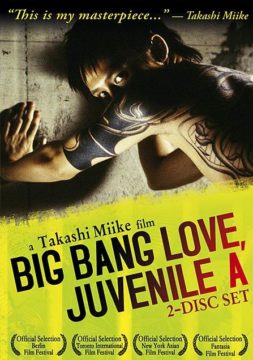

Original Title: 46-okunen no koi – 46億年の恋

2006 – Japan

Genre: Drama

Director: Miike Takashi

Music: Endo Kôji

Screenplay: Nakamura Masa

With Matsuda Ryuhei, Ando Masanobu, Kubozuka Shunsuke, Endo Kenichi and Ishibashi Renji

Story: In an unknown future, Jun confesses to the murder of another boy, Shiro, an all-boy juvenile detention facility. The story follows two detectives trying to uncover the case through interviews and intersperses testimonies by the inmates and the prison employees with events in the lives of Jun and Shiro. Jun, who is incarcerated for the murder of his rapist, forms an intensely close bond with Shiro, who is in prison for a murder and the rape of a woman. Shiro protects Jun with fanatical intensity and violence from the other boys, though his intentions toward Jun are not clear. The highly symbolic visuals and dialogue contrast with the routine nature of the police investigation, creating a somewhat surreal commentary on the nature of violence and salvation throughout the film.

Xe had to wait till, like, 2006 to see Miike Takashi’s first auteur film in a way, a really beautiful one, like some of his previous works, such as Rainy Dog, Bird People of China or Dead or Alive 2. But till then, most of his films were easily to notice, with their themes, or period. We were often facing Yakuza films, taking place nowadays, and the themes were often family. Of course, some films were weirder, like IZO in 2004, a crazy film hard to understand, beautiful, but also cruel, but this new film here is right between his logical work and IZO, and it makes sense inside his filmography. Surprising, beautiful, hard to understand at times, strange, but also simple, here are a few words to describe the experience. Big Bang Love, Juvenile A isn’t the easiest work from Miike, but on the other hand, it’s his simpler work visually, and it’s crazier in story telling, next to IZO. Here, Miike can experiment everything he wants, and he delivers a strange film, so simple to explain, but so complex by many small details in the story and in the style of the film.

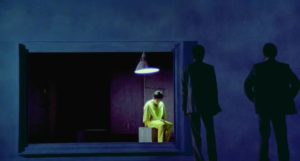

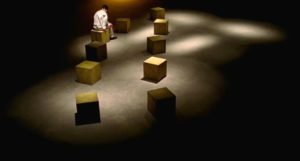

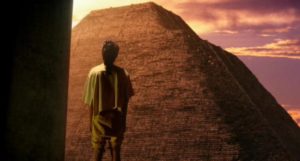

Jun ad Shiro are two young people, but total opposites. They arrive on the same day in prison to serve the same punishment. Jun is a very quiet boy, here because he killed a man who abused him. Jun doesn’t speak. Shiro is a here because of his brutal behavior, using his first to express himself. Complete opposites, yet they are closely related, and are going to stay together. Jun will not change, remaining the silent guy he is while Shiro will let his firsts talk against the other prisoners, not initially tender to Jun. And of course, Jun will start to develop a silent admiration for his new friend. The film is an initiation quest for Jun, evolving in a world often described as a cold one in movies. Not here. Miike lets his imagination to whatever it wants, and his prison is radically different, visual, attractive, but at the same time, empty. Empty like, empty locations, no walls, no floors, no meaning. When they arrive in the prison, they pass among prisoners, stored around a long hallway, without walls, just separated by lines on the floor and lights. The director’s office is weird, walls are skewed. In this extraordinary world, these characters will stay together, become friends, and we’ll see all that with dreams sequences. Dreams about the outside world, about a rocket launch in space, a Mayan pyramid, and blue butterflies…

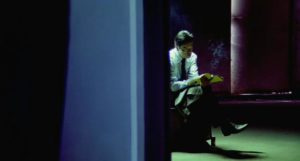

A strange world offering us its story on a plate, but the treatment will be harder, way harder. Jun and Shiro arrive in prison, and shortly after, jun will be found killing Shiro. More than a description of violence, Miike will take his time, time to explain the violence. Explain the reason behind it, how it may arrives where we don’t expect it. A police investigation will be at the heart of the film, the heart of the drama between two close people. An investigation leaded by two regulars from Miike’s film, Endô Kenichi (Visitor Q) and Ishibashi Renji (Dead or Alive, One Missed Call), already together in Ishii Takashi’s Flower and Snake. But the investigation is not the most important part of the story for Miike, but the vector leading to an explanation of a human drama. The investigation even allows Miike to visually exploit many things, including scenes we’ll see from different point of view, with or without the characters, and even a Q&A where the questions are displayed on screen. Fragmented like a puzzle, Big Bang Love, Juvenile A proves to be an unusual work, a miracle inside Miike’s filmography, which will destabilize the audience, a work which there is so much to say, the words don’t always mean something, like the feeling of the characters.

The best

Great directing

Original and experimental

Matsuda Ryuhei, perfect

Meeeh

Maybe we see some scenes far too often

So: Miike delivers us a true auteur film, with beautiful images, a fragmented narrative. It’s a human tragedy and an initiation quest.